News

Albinas Kentra-Ausra, a partisan and chronicler of the Lithuanian Atgimimas (Revival) movement, has been awarded the annual Freedom Prize in Lithuania. E-portal 8diena.lt talks to Mr. Kentra and shares his incredible life story which is an important part of Lithuanian history as well.

The Lithuanian Seimas (Parliament), in response to proposals from individuals, communities, academia, organizations and associations on national and municipal levels, has decided to award Albinas Kentra the Freedom Prize. Mr. Kentra, who is a freedom fighter, was recipient of the Order of the Cross of Vytis in 2019. We congratulate the awardee and legend: a partisan, establisher of modern teaching technology in the Faculty of Philology at Vilnius University, an analyst of the history of the road to freedom for Lithuania, preserver of the memory of the forest brothers, who recently celebrated his 90th birthday. Here we share some thoughts of Albinas Kentra with our readers.

** *

By Gediminas Kajėnas | 8diena.lt | January 28, 2018

Translation by Neila Baumilienė and John Baltrus

Albinas Kentra-Aušra (1929) is a legendary personality in its true sense. At the beginning of the Independence movement, he was in the front lines video recording the most important events of that time. In his video archive, originating from 1965, there are 20,000 hours of video recordings. He immortalized our road to the Singing Revolution and the events that followed it up to this day. But this is just one side of Kentra’s activities: the public one. Barely 16 years old, in the woods of Šilalė, he gave the oath of a partisan and stayed true to it during his torture in the Gulag in Soviet times. He exchanged post-war armed resistance for other forms of resistance. A. Kentra devoted his whole life to the fight for freedom – the work started by the Forest Brothers and Sisters. As he states: “The mission is being achieved quietly, without boasting, without expecting recognition for merit, but with consistent everyday work while getting an assignment accomplished.”

Tell us your story from the very beginning, from your childhood. The fundamentals that predetermined your choices and must have formed them.

I was born in the Independent Lithuania in 1929. I had five siblings: three brothers and two sisters. One sister was younger than me, all others older. My mother, Onutė Šerpytaitė, was born in 1901 in Chicago and was brought to Lithuania by her parents while Lithuania was still ruled by the Czar. The blue-eyed beauty, when she was eighteen, was visited by Juozapas Kentra, a matchmaker, with a young man as a suitor. When they left, her parents turned to her to ask how she liked the young man. She replied: if the suitor were like the matchmaker, I would marry him. She ended up marrying the matchmaker.

I grew up in a big family, including my grandparents, on a 66-acre farm in the village of Gūbriai not far from Šilalė. My mother’s flower garden had signs and symbols of Faith, Hope, Love and Gediminas’ pillars. My mother was an active participant in cultural events, wrote poetry, gave lectures in Šilalė, organized educational events, was interested in the events of the world, and belonged to the executive committee of the women’s organization in Šilalė. My father was involved in land reform, imported cattle from Holland, and organized a Dairy center in Šilalė. He was all about the rebuilding of his Homeland to finally free it from Czarist Russia. The family subscribed to every Lithuanian newspaper, while children were educated in the Christian and national spirit.

Our home was a place where children from the neighborhood would gather to play. Before our playtime, my mother would have us sit and give us a certain text to read. That is when we were introduced to “Les Misérables” by V. Hugo and other books, Lithuanian history, and Christian literature. We were then free to play and later on were treated to a meal prepared by my mother. That is how we grew up. We could hear songs from neighboring houses, people were attentive to each other, and the whole community would come to help out a neighbor.

This idyll lasted until 1940. You were eleven then.

My father predicted WWII ahead of time. He wanted to save the family and urged us all to go to America. Our Mother was born in Chicago and we had a right to emigrate to the US. Our uncle M. Kruša, who was a prelate, originally from Zasynai, helped establish Lithuanian heritage schools across Lithuanian Catholic communities. Together with a delegation, he went to see the U.S. President, W. Harding, in order to have Lithuania recognized de jure. Meanwhile, my mother who loved her country, said that if she had to die, she’d rather die on her own land.

Four years after my father’s predictions, my oldest brother Jonas was the first one to hear the news about the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. He heard it over his hand-made radio. I remember when he came up to me and said in a sad voice: “Albinas, there is no more Lithuania”. It was then that the singing stopped in the villages, and unrestful times began on our land.

The occupants and their collaborators tried to convince people that Lenin came to our country for all times. Those who thought otherwise were imprisoned.

We, the schoolchildren of Nevočiai, started practicing defense of the Homeland. We would split into two groups of defense and offense. Once, during our fight, I got hit in the chest by a rock, and I could not catch my breath. I remember lying on my back and looking at the blue sky and thinking that I was seeing it for the last time.

On February 16th, 1941 I hung a garland of tri color flags in between birch trees by the school. It was then when I was interrogated for the first time. Four militia men came to our school, and took me out of a class to the teacher’s lounge. I remember standing among them with my head tilted back, looking at their nonLithuanian faces and denying that I had hung the garlands and tampered with the picture of Stalin, which had been hung in place of Antanas Smetona, the President of Lithuania.

Our family, just like the majority of Lithuanians, believed that the red terror wouldn’t last long. Lithuanians waited for the war, although until then they would pray: “Lord save us from a war, a plague and a famine.” Under occupation, Lithuanians waited for the war to start, thinking that only during the conflict between the Soviet Union and the free world, they could become free. People were preparing for that. Our father had suffered from wrongdoings of the occupants, and before his death in December of 1940, said: “Now it is better to die than continue living... “

In 1941, the arrests and deportations to Siberia were a planned elimination of the Lithuanian nation with a purpose to resettle other nationals from the Soviet Union into the empty and very appealing Lithuanian cities, towns, and villages. It was a painful time for Lithuania. For our family, the news about the war between Germany and the Soviet Union, was good news. As well as the fact that in Kaunas, Lithuanians rose up and chased the Red army out of the city, before the Germans even got Kaunas. The good news was also the arrival of an interim government of Lithuania. One more important piece of news was about the Wehrmacht getting rid of the Red Army from Lithuania, and this way, putting a stop to further deportations to Siberia. I remember when soldiers of the Wehrmacht on motorcycles came to our yard and asked us if there were any Communists around. There were some but nobody betrayed them.

Our hopes though did not come true, Lithuanian independence was not reestablished, Lithuanians could not freely rule their country, or in any way prevent further misfortunes and killings.

|

With the Red Army approaching, encouraged by our neighbor Ms. Stulgaitė, we could have fled to the West. My brother Jonas, a scout, following the oath, chose to be dutiful to God and the Homeland. At that time, our family had three choices: to flee to the West, to stay in Lithuania and endure humiliations of the occupants, or to defend our Homeland with the oral and written word, or with a gun if necessary. We made the hardest choice and in June of 1944, we started digging a bunker. The sand dug out from beneath the floor of our house was taken to an enclosure near the barn and hidden with topsoil. It was very important that nobody would see the bunker being dug. It was supposed to serve not only as a bunker but also as a defensive fortification. The hidden entrance to the first bunker was in between two walls from a sunroom and a foyer. In the floor, the first bunker had an opening to a second one under the floor. There was one more opening to get to an even deeper hiding place, which was made of bricks and could fit the whole family or a unit of partisans. In case of danger, there was an exit to a defensive fortification – a fox hole which was under the floor of the sunroom. From there we could defend ourselves from an approaching enemy or leave the farmhouse.

In the autumn of 1944, the Red army occupied the region of Šilalė and was moving towards Germany. The communist government came back from Moscow along with all the organizations that committed crimes in Lithuania in 1941. It was time to be armed and be ready to defend freedom of Homeland. Lithuanians started to arm themselves in 1941 when the Russian army was sporadically leaving Lithuania, while being chased by the German troops. The Russian army had left ammunition and weapons behind. Villagers would pick them up, hide them and save them up until the after-war occupation. When in 1944, the German army retreated and the Russian army returned to Lithuania, there were Russian and German ammunition and weapons left on the battlefields. During that time, I remember three very memorable cases of armament.

In the autumn of 1944, a unit of Russian tanks stopped for a day not far from the gymnasium near the pine grove of Šilalė. Among the tanks, there was one German tank, the newest Tiger, taken over by the Russians. From the gymnasium, I went straight to the yellow Tiger, jumped into it, and started unscrewing its machine gun while the tank drivers were not around. Suddenly, one of the drivers appeared, noticed me in the tank and waved his hand for me to get out. He took me to the grove at gunpoint while firing shots over my head. I thought he was going to kill me, but I was not scared. He finished one ammunition clip, then the second one, and once we were at the border of the grove he said: “Mom, Dad?” Without knowing any Russian, I waved my hand towards our farm house further on the hill surrounded by oak trees. We both walked. My mother knew Russian since the time of the Czar, so they spoke to each other, 4 she treated him to a meal, and he let me go. Without saying anything to anyone, in the evening I went again to the same tank. I noticed that the tank drivers were in their tents for the night. I snuck into the tank and finished unscrewing the machine gun. I pulled it towards me but it was stuck. I got out of the tank and noticed that the silencer of the gun was in the way, so I unscrewed it and put it in my pocket. I got back into the tank and then right out of it with the machine gun in hand. Hiding by the bushes I hurried straight to the partisan regiment where my brother Rūtenis was located. The machine gun was used in the woods of Šilalė, Kvėdarna, Laukuva, and Rietavas for the longest time, until there were no more reserves of German ammunition.

That same autumn, I found out from one of the students of Šilalė gymnasium (high school), that there was an MG machine gun hidden in the attic of the gymnasium. The only time it could have been retrieved was during the day right after school hours while the door was still unlocked. Next day I came to school by bike. I wrapped the machine gun in a cloth, took it down to the bike, secured it to the frame and calmly passed by all the Russian soldiers on the street of Šilalė.

The next episode could have ended badly. That night I was carrying 400 bullets for a machine gun which I gotten from a friend. Two mounted guards suddenly entered my street and yelled out to stop. I ran while being chased by horses towards the bridge at Kvėdarna. Without losing the bullets, I jumped into a trench by the bridge embankment. I looked up at the silhouettes of the NKVD men and their horses, and I felt sorry that I had not taken a gun. If they saw me, I would have tried to escape. In a little bit, the breathing of the horses stopped, I could hear nightingales sing, but the men were still listening. Soon a carriage of their collaborators came. I thought they would all get out to look for me, but after having exchanged a couple words with the guards, they left. Then the guards moved onto the bridge, a few steps away from me. I wanted to get up and walk in the trench, but realized that I lost my shoe. I tried looking for it in the grass, quietly. I could not leave it there because in the morning, they could have found it and identified me. The shoe was made by a shoemaker, Gerikas, during the German time. I finally found it, and following the bank of the Lokysta river, happily reached the partisan unit.

I might as well name one more case of armament. We, four brothers, poked the soil of the Jakas farm with an épée for the longest time until we found a machine gun “Maksim” with wheels and armor. My brother Tauras carried it on his shoulders for more than a kilometer through fields along the road of the village of Derkintai, towards the bridge over the Lokysta, when a carriage appeared coming towards us very fast in the dark. We fell on the ground and got our guns ready. Once the NKVD collaborators passed by, we could hear the voice of Gerikas: “We will get rid of the Kentra brothers”. We had to avoid cross fire with those traitors, who were killers of decent Lithuanians, because an innocent driver could have been killed since he had been forced to drive them.

|

When the Russians took over, you and your brothers still lived at home for some time?

The occupants and their collaborators understood that our family would never be loyal to their government. Although danger had been approaching in the fall of 1944, we still were able to live at home. In the winter, the elder of the village asked my brother Jonas to drive around the village and make some records. Avoiding being recognized as a partisan, he agreed to join him. As soon as they left, two NKVD men entered our home looking for Jonas. Since they did not find him, they left. My sister Onutė recognized the danger and ran out for Jonas. After one kilometer, in the dark, she spotted a sleigh but could not tell if it was the one with Jonas or the NKVD men. She approached the sleigh, found Jonas there, warned him and hid with the neighbors. The neighbors spotted the NKVD sleight as well, they sat Onutė on the edge of a bed, gave her a bucket with potatoes and put a big shawl over her head and shoulders. She was looking down while peeling potatoes. The NKVD men entered the house asked about the girl, looked around, did not spot her and left to chase the other sleight. That was how Onutė saved her brother from being arrested. The brothers continued the fight for freedom in the underground.

My brothers often would come home alone or with other partisans, and sometimes would stay home for longer periods of time. Sometimes the NKVD would storm the house, but my brothers would be able to get into the bunker. After searching in vain, the men would stay longer in the veranda where one wall was made of stucco, but they never understood that there were two planks behind them which opened the entrance to the first bunker in between two walls. On those planks, covering the seam, there was a wooden plank for coat hanging, as it covered the entrance to the bunker. The NKVD suspected that the brothers could be in an undiscovered bunker. One winter night, brother Jonas, while walking from his room to the bunker through the veranda, pushed down the door handle, but sensing something wrong, did not open the door. He got closer to the window and saw an NKVD man by the house with a rifle, while a bit further away other men were robbing the bee hives. The NKVD waited for the partisans to come out to protect their bee hives from the robbers.

My mother, sisters and I lived on our homestead until the spring of 1945. In April, we found out that they were coming for us. Without hesitation, we ran out of the house, without having time to unchain our dog. He protected our home until he was killed; he should have had a monument. I ran out of the house and hid in an adjacent grove not far from the house where I waited for my sister Elena to walk by on her way home from the gymnasium. I had to warn her not to return home.

It was from that time that the forests and bunkers, as well as the homesteads of good people, became our home.

|

The whole family without a home ... it must have been a very hard period of time?

When the Second World War Allies celebrated victory, in Lithuania, the war after the war had already started. The Lithuanian nation was fighting for its freedom on its own, without any military support from the outside, against the most powerful totalitarian country in the world, the Soviet Union, which had already been known as the Empire of Exceptional Evil in 1941. Much more time was going to pass until R. Reagan, the President of the US would confirm it.

Common sense would not allow Lithuanians to think that the totalitarian regime of the Soviet Union, which had killed millions of innocent people even before WWII, would remain unpunished, and even be supported, in order to become stronger and to escape collapse, while Nazism had been uprooted for good. The outcomes were horrible. The Soviet regime had been imposed not only in the Baltic states and Eastern Europe, but on every continent. The armament became inevitable and has consequences to this day.

The partisans understood the fate of their fight. From that era, my sister Elena remembered a conversation among the Samogitian Partisan chiefs regarding survival. Rūtenis, who was my brother Jonas Kentra, saw only one possibility to survive, and that was for a small number of partisans to go to the Western border guarded by the Russian army and try to break through it. He said it would not be honorable, though, because the chiefs would not be able to take all the partisans with them. Meanwhile, at that time, sentenced by the Russian war tribunal, I was already in the grisly labor camp of Spask.

Tell us about the period when you were a partisan. It was at the very beginning, while there were not that many big and painful losses, men could walk in big groups and would fight the NKVD and their collaborators openly.

People who joined my brother Rūtenis’ unit were selfless. His unit fought without any losses for a long time. I remember once Rūtenis told his men to never shoot Russian soldiers in their backs, if they were running. He thought they were mobilized to the army by force. At that time, Rūtenis did not know that our men were fighting against the criminals of war – the Army of Vetrof. Those were the criminals who at some point, when deporting the Chechen people and not being able to get into their villages in the mountains with their vehicles, got there by foot, forced villagers into buildings, and burned them. Later on, the same army was assigned to fight in Ukraine, then to Lithuania. Rūtenis was always concerned about safety of the partisan supporters. He used to say, that it is better to die than to lose them, since without the help of the supporters, the fight for freedom would have never have lasted a decade.

In 1950, Rūtenis told our sister Elena that he has a new nom de guerre, and that his territory is from the Baltic Sea to Raseiniai. He led the Būtigeidis unit. He was wounded 17 times and became a legend of the area. Signalmen called him “Vytautas the Great.”

The partisan conversations in the bunkers are very memorable. They would not associate their fight with their own good but with the liberation of Lithuania. Only a small piece of paper is left from Rūtenis’ writings, the history of the fights of the partisans, recorded over seven years. Only an unfinished sentence survived to this day: “With the advancement of technology and an increase in superficiality, one cannot coordinate actions with the deeper human nature, and creates chaos within oneself and in the world, and by exaggerating the bodily fight for existence…” This tragedy understood by Rūtenis is even more visible in society nowadays.

How long have you been a partisan?

When our family left our home, we continued our fight in the underground. I took the oath, my sister Elena took the code name Snaigė, sister Onutė – Rasa, brother Jonas – Rūtenis, Juozas – Tauras, Leonas – Sakalas, Albinas – Aušra. Mom was always called Motinėlė.

I finished being a partisan on July 7th, 1946. On that day our unit came back from a night march, we scattered to spend time on the homesteads in Šilalė. I had an assignment to go Šilalė to see a man in the underground. Rūtenis said that it was dangerous and he had a hard time letting me go, saying that he let me go during the day for the last time.

When I reached the Šilalė church, I bumped into a school boy, who was supplying us with ammunition. He was happy to see me and shook my hand for a long time. I thought just because we had not seen each other for a long time. Soon I noticed the NKVD follow me while I walked along Šilalė pond. I did not turn around but understood that I was in danger. Suddenly I spotted a man far in the distance, started running towards him and yelling: “Petras, wait for me!”, although I knew he would not hear me. I ran fast without looking back and could hear the NKVD running after me. When I reached a field with a tall grass, I dropped my gun and ammunition and destroyed the paper. Once at the outskirts of Šilalė, they surrounded me, searched and did not find anything. Then they stood me against a tree and threatened to shoot me if I did not tell where the rest of us were. Looking at the hollows of seven muzzles I kept answering that I did not know. They threatened me again by taking me to the woods and saying they would kill me.

When a carriage for hay came from Šilalė, they put me on it, covered with hay. Curled up, I cleared some hay and watched the shoes of the NKVD men. Soon I noticed that the carriage came to the NKVD headquarters in Šilalė, where I was ordered to get up. While I was getting up, they put an NKVD hat on my head, and a coat with red epaulets over my shoulders, and took me to their headquarters. I remember all the scary faces in the room and I was thinking to myself that I had to conquer them. I could not betray my brothers, sisters, and others, even if I was tortured with a hot iron or needles under my nails. I was not the first and not the last one dying for the Homeland. I was just afraid to lose consciousness and start answering questions of the cruel Russian NKVD men and a few Lithuanian traitors. Just recently I stood against the trunk of the tree and looked at the hollows of guns pointed at me, now I was looking at their black eyes dazed by anger, infuriated, shining from sweat, disfigured faces, and tried to protect my head with my hands to stay conscious for as long as I could. It was after the midnight when I left that house by the pond, with broken sticks, and a long, painful rubber hose waiting for others. On the other side of the road, in front of the Šilalė Ūkis bank there was a red brick building of NKVD collaborators. A guard with a rifle at the door, lifted the lid of the basement with his foot. In the dark corner, on the cement, I found a damp tuft of hay and sat down on it. I was wearing only a shirt. I brushed my hair with my fingers, scooped all the strands that fell off during the beating into my palm and stuck them in my pocket. I saved them until they disappeared along with my jacket in the Spask labor camp, far behind the Ural Mountains. I fell into a deep sleep wile thinking about the forest brothers. Only rats running around me would wake me up from time to time.

|

Did I understand correctly that you were caught not by mistake?

I only understood it when I was in Tauragė, in the NKVD interrogation and imprisonment headquarters. There they interrogated me in two shifts day and night so I could not sleep. They kept saying: “Who will overcome whom. You us or we you?” Once, after a night interrogation, one of the interrogators while taking me to my cell and pushing me through the hallway, yelled: “To whom did you give the Nagant revolver with 20 bullets?” “I did not have any and did not give it to anyone.” This sentence disclosed the spy: a school boy. I understood that it was not only my brothers, but all the partisans of the area who were in danger. They made a decision to accept the school boy who had shaken my hand into the higher structures of the partisans. Once, this “partisan supporter” gave me a Russian automatic gun and asked me for a short gun. I took the revolver from my brother Rūtenis and gave it to him.

The Forest Brothers did not know about the betrayal approaching their ranks. I could not wait to see uncle Pranas, who would come with a sack so I could give him a letter to give to them, which I sewed into the hem of a sack of laundry. The method of communication was established when I found a short piece of graphite in the hem of the sack along with a needle and thread. I did not wait long before I sent the Forest Brothers a small piece of paper with a drawing of a dog and three letters: “Dam.” Once uncle Pranas came back, the message in the hem read: “to liquidate?” My message followed: “not necessary for me”. As before, they interrogated me day and night, while Dam was getting deeper into the woods. Rūtenis did not stop communicating with him. It is a pity that when Rūtenis died, his writings were burned.

While I was being interrogated, the NKVD would read out loud lists of names and asked if I knew any of them. Once they read “Apolinaras Damulis.” I answered right away, that I knew him, and that he threatened to put me in jail. The interrogators got confused. Looking at their faces, I told them a made-up story. They calmed down.

For the first time in the sack that was brought to me, I found a clean shirt and some food. I satisfied my hunger and felt more alert. The events started unfolding fast. In two days, the traitor who had just recently shook my hand in Šilalė, was put in front of me. The interrogators observed our confrontation. I moralized him and he was defending himself. One of the interrogators threatened him. It looked like they started doubting their agent. They could not understand if the arms that were given to him were serving as bait and whether he was giving them to the partisans to gain their trust.

Well, soon they brought another witness for a confrontation with me. He was a young man broken during the interrogations and he testified that I had been to the forest and taken the oath. The rest was as usual. The book of my investigation’s history was getting bigger. After the confrontation with Dam, the NKVD plan to eliminate the partisans was over, and the NKVD felt defeated and mad. The sack brought by uncle Pranas had no more food, the NKVD guards would take it all.

The NKVD did not have any proof of your guilt, only the testimony of the traitor?

When I was back from the Gulag, I found out from my sister Elena-Snaigė, that my brother Rūtenis even after my confrontation with the traitor, continued meeting with the traitor who would bring weapons, still assuming that the partisans did not know anything about his betrayal. He would ask how Albinas ended up with the NKVD. Rūtenis wanted to add stories of the betrayal psychology to the Fights for Freedom History he was writing.

Even before the Baltic Way (1989), I was approached by J. Šerpetauskas who lived in the village of Traksėdis in Šilalė. He used to be Rūtenis’ signalman. He said that in his home in a bunker, the Chronicle of the Fights for Freedom by Rūtenis had been hidden, and he promised to give it to me in two weeks. When I went to see him, I found out that the chronicle was not there. J. Šerpetauskas told me that when he moved to the neighboring homestead and new people moved into his. The new owner while doing renovation, ripped up the floor of the attic and seeing volumes of writings and photographs, got scared and burned them all. That is how the Chronicle of the Fights for Freedom written by Rūtenis for seven years, perished. It was a painful loss to the history of Lithuania.

Let’s get back to your story.

The Russian war tribunal in Šilutė sentenced me to ten years for the betrayal of the Homeland. After the trial, I was given a “Plea for Mercy” to sign. I answered that I was not going to bow to the occupants. At that time, there were two sentences: execution or ten years in a labor camp.

They took me from Šilutė to the Lukiškės jail in Vilnius. Trains would go to the labor camps of Siberia from Vilnius. I was on the list to be taken to the copper mines in Jekasgan where prisoners would lose their health really fast. One of the days, they lined us up in fours, into a long column right under the dome of the church of the jail in order to choose the right prisoners for the mine. We would be approached by a team of “buyers”. Once I put my wounded right hand out, I was taken out of the formation.

That was how I ended up in the jail at Rasos, then in the Spask labor camp. Once the relationship between the East and the West deteriorated, the political prisoners were taken out of Rasos. Our train stopped far from the Ural Mountains in Karabas. We became known for the famous march by foot from Karabas to the Spask labor camp in 1949. A long formation would march through a melting snow. I was holding an elderly man from Kaunas until the evening. At the fall of the dark on the night of April 1st , there was a freeze. Armed handlers lied to us saying that the lights far in the steppe was going to be our destination.

The handlers had to fire machine guns over our heads in order for us to get up from the snow where we would fall down to rest for five minutes, and then to continue moving forward. That night, I was also extending my arms to the snow, willing to fall into it as if it was a down bedding, but the thought that my family wouldn’t know where I was, stopped me from doing that. By dawn, along with the frozen-to-death ones in the sleight, we reached Spask. They wanted to amputate my frozen toes, but I did not let them. That is why I walked so fast for most of my life.

What was this labor camp known for? Is it true that you were imprisoned together with the future writer A. Solzhenitsyn?

Yes, we lived in the same barrack with A. Solzhenistyn. It was an international labor camp for political prisoners and one could meet people from different nations. Most of them were educated intellectuals, scholars of different specialties, diplomats, military men, and people of culture.

I met my teacher of the German language and literature in the cargo car on the train. Before falling asleep, with their heads down, men would sing “Lithuania, our Homeland”. The lips of only one man did not move. He was a 50 year-old Bavarian named Joseph Dreksel. During the war, he was a colonel. During peace time, he was a teacher. Every day he would write down excerpts from “Faust”, “William Tell” or another piece of literature, and 100 words in dual vocabulary for me from heart when we were in the Spask labor camp. I would memorize them in the morning, when the guards were counting us outside the locked barracks. In the evening, my teacher would be very happy to listen to me reporting to him my completed assignment. Joseph, along with other prisoners, was harnessed to the sleights to pull boulders for the construction of new barracks. He would call me his son and wanted eventually to invite me to Germany to study in a University. He would be proud when in a chess competition I would become the champion of the labor camp or when I would win in simultaneous play on 20 boards.

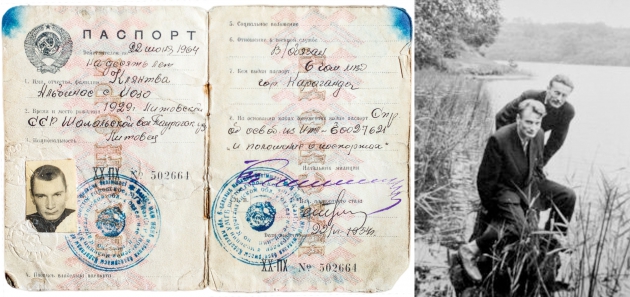

His wish for my luck on my birthday was fateful. He came to me, took a golden heart with a glass cover hidden in the armpit of his military uniform and said: “Albinas, today, I would like to give you the most precious thing I have. When I left for war, my wife gave it to me as a talisman for luck. In the front, when in the firefight I would always survive, and from now on this luck will be with you.” When I was released from the labor camp, other Lithuanians along with my teacher saw me off. He said to me “God bless” and repeated the words I said to him a couple of years ago: “Tauragė, Šilalė, Gūbriai.” When I left the labor camp, they gave me a passport with my last name written “Klentva,” which was changed from my name while I was in the prison at Lukiškės: “Kiantva”.

How did everyday life look like in the labor camp? What work did you do there?

People fell down like leaves. The hospitals were full. We, a group of young people, gathered together by Liudas Dambrauskas, did medical analysis. We would ask patients where they would prefer to be: at work or in the hospital? If they’d say, “in the hospital,” then we would write down that they belong in the hospital. People starved. Once, in a wooden enclosure, I found a bucket full of hot pasta. I sat down and started eating, but not for long. Suddenly, I saw two wolf dogs approaching me. It was their food, which was better than what was for the humans.

While in the labor camp, I would always dream of black bread. The managers of the labor camp were cruel. Actions of a KGB agent, Kruglov, were shocking. Once in the women’s zone, young nuns from Ukraine resisted his sexual harassment by ripping his epaulet off. On a cold winter morning, he took them away outside the camp zone with their hands tied with wires and came back with an empty truck only with their black dresses and crosses in it. The cemetery of the labor camp expanded by a grave. Very memorable was a meeting with a historian from The Academy of Sciences of Georgia. He told us about U.S. President T. Roosevelt and his wife’s visit to the Crimean Conference, where he was introduced to the blossoming economics of the Soviet Union. In the collective farm, his wife was greeted by nicely dressed and singing farm girls – actresses from a theatre.

|

When were you released?

In 1954, I left the labor camp with a new last name “Klentva”. While still in the Spask labor camp, I received a letter from my sister Ona-Rasa not to go Šilalė, but to go straight to Šiauliai to see the signalman. I went there, drank a cup a tea with him, and said that I was rushing to see my brothers. His face fell. I asked what happened. He said: “they all have perished”. My mother used to write to me in the labor camp in Russian: “I am walking in the woods full of birds that sing and fly, where they make warm nests.”

I found my mother, who was hiding, and with her we went to Kaunas to see Algimantas, the brother of my friend from the labor camp, Gediminas Andriuškevičius. Later, I lived with the Kairiūkščiai family for a little bit. In 1955, my sister Ona came back from the Polar Circle. A year later, sister Elena returned also, and we rented a room in Vilijampolė. My mother kept hiding until she died in 1961. She would live with us or in village of Šilalė, where I would visit her often.

When I was in the labor camp, everyone kept telling me to go to school when I return to Lithuania because I was smart. Although I was 25 years old, I looked younger. In order to continue higher education, I needed to finish secondary school first.

How did you do it? You had a “tranished” biography.

I went to Šilalė and got the certificate of graduation from middle school. I just had to correct my old last name and make it look like the new one, which I received in the labor camp. I just needed to insert the letter “l” and turn “r” into “v”. In secondary school in Kaunas, I gave my documents from Šilalė to a secretary, and said that I was entering my Senior year. She put my papers with the graduating class. Therefore, I secretly had to finish four grades worth of studies in a year. I did not tell her that I could speak German, and picked English to learn. I had to learn by myself geometry, trigonometry and algebra in the first few weeks of the school year. When they were collecting Lithuanian literature writing assignments, I did not turn any in since I had no idea how to create an outline for the assignment. During English classes, I was doing fine because I used to talk to a prisoner named Evans, originally from London. I had also read “The American Tragedy” in the labor camp.

After the first trimester, I became an A student and finally graduated from secondary school. I intensively studied medicine in the labor camp. I was hoping to return to my brothers in the forest. Meanwhile, I had to choose a field of study: medicine, German or English language and literature, or something else. The most important thing was not to make the Admission Commission suspicious of my past in the resistance movement. Advised by Balys Stulpinas, associate professor of Chemistry, I went to see the vice dean of Faculty of History and Philology at Vilnius University. He advised me to apply for part-time studies because those students were checked on the least. My choice of studies was English language and literature. In my vitae, I wrote that I attended the gymnasium in Šilalė, where I was wounded and became disabled, received government support, moved to Kaunas, and graduated from a secondary school. I was accepted.

After I finished the first year, I received a phone call from the dean of the faculty professor J. Palionis, who asked me to come to the department. I thought that they figured me out and were crossing me off the student list. He took me to the University rector and said: “The faculty wants to have this student on fulltime basis”. The dean did not know what he was proposing, or the rector, what he was accepting...

In Vilnius, I lived with my friend from the labor camp because I could not request a university dormitory because my passport issued in the labor camp forbid me to live in the capital city. Once, when crossing the Cathedral Square, I was greeted by a classmate from the gymnasium in Šilalė, with “Hello, Kentra”. I was happy that nobody was around, but it was then that I decided to “lose” my passport from Spask and to get one issued in Lithuania. My current passport noted that I went to a labor camp. In the passport department of the Kaunas Militia (police), I said to a young passport officer that I had lost my passport. She asked me to bring my birth certificate and said that she would correct the last name according to my birth certificate. A couple days later, I had a new passport in my pocket and legal permission to live in the capital city. Once again, I got lucky, since the young officer at the Department of Passports, who was substituting for the chief officer, did not look at the registration of the passport. During my years of university studies, I realized that the blood shed by thousands of partisans, and the sufferings of prisoners and deportees were not a meaningless sacrifice for their Homeland. Once, I asked a Russian student, why his family moved to Prussia after WWII. He said that they tried to settle in the villages of Lithuania, and to create collective farms, but they would be visited by the partisans, whom they called the bandits, who would order them to leave the village in 10 days. That is why Lithuanian villages stayed Lithuanian during the years of occupation. This was exactly why during the independence years, Lithuania was inhabited by 80 % Lithuanians, and we were able to reestablish independence.

|

In 1960, I graduated from Vilnius University and was assigned to teach German to the Juniors in Nemenčinė secondary school, and to teach English in the Laurai school. During my second year as a teacher there, the Ministry of Higher education of the USSR at the Universities of Leningrad and Moscow established a two-year long course in English for professors at higher-education institutions. Although I was not a professor at the higher-education institution, I tried my luck and entered the admission contest. Applications were accepted from all the republics; admission was limited and competitive. I passed the entrance exams and became a student of a course in the pedagogy of higher education for two years at the University of Leningrad. I was an English studies teacher for university students during my internship.

Along with my mandatory studies, I passed exams (linguistics, Old English, Gothic, philosophy etc.) for postgraduate studies. During the Old English exam, the commission allowed 30 minutes so I prepared by translating the text into Russian. When asked to present, I sat at the table in between prof. B. G. Reizov and prof. Irina Ivanova, who was the head of English Department at the University of Leningrad. She said I could translate into any language except Lithuanian. I opened the book of Old English and translated the texts assigned for me not into Russian, but into German. I had thought I had cold blood, but I was nervous and completely forgot that I had already prepared the translation into Russian. This anxiety predetermined my further studies at the University of Leningrad. Two days later, prof. I. P. Ivanova asked me to come to her home and for two evenings, she helped me study Gothic. We analyzed the Bible written in Gothic and other linguistic disciplines. When I passed the exams, I was offered to do my PhD in linguistics. I wanted to delve deeper into the roots and development of Lithuanian language, but a renovation of the Faculty of Philology at Vilnius University changed the direction of my plans. Studies were very appealing, but it seemed to me much more important to establish a center of audiovisual laboratories for studies of foreign languages. That is why at the public library in Leningrad, instead of writing my PhD thesis under the supervision of prof. I. P. Ivanova, I was designing the labs.

While walking along Neva Avenue and passing by the restaurant Neva, I finally made up my mind and chose Vilnius. I received a letter of reference by the Ministry of Higher education of the USSR and was assigned to Vilnius University. That is how I landed in Vilnius University, as if by parachute and without being checked by any of the commissions, and how I became senior lecturer in the Department of English language. To continue the work of the Forest Brothers, I focused on the establishment of the audiovisual laboratories and decoration of the interiors of the University.

Please, tell us more about your efforts to establish the audiovisual laboratory at Vilnius University, which was unique in the whole Soviet Union, and where real English could be heard.

When I was studying English at Vilnius University, I noticed that spoken English had not been taught there. I checked all the audio records made in the Soviet Union that were meant to teach English. In all of them, every word of the sentence was pronounced separately. I realized that the students were taught written English in order to be able “to read about the achievements of the capitalist world and to copy their inventions,” but they would not understand information in English from the radio stations of the free world. In order to break the iron curtain in the area of information flow, it was necessary to establish audiovisual laboratories and smuggle programmed audiovisual courses from abroad. At that time, it was very important for Lithuania, since while the Soviet Union had been jamming stations to prevent free information flow from abroad transmitted in Lithuanian and Russian, they could not jam stations of their Allies transmitted in English. That is why Soviet educational institutions taught English that was impossible to understand.

The audiovisual consoles had to be made, but electronic parts were not being sold anywhere. Mindaugas Mockus, an engineer from the “Sigma” factory helped me overcome those difficulties. He would often figure out where they made a certain transistor or a part, but did not know the exact addresses of those factories. I was traveling around looking for secret factories. Once I visited Tula. In the morning, crowds of workers would go to their factories, so I joined them. I joined one big formation of workers and started chatting with a worker. I said to him that I knew that a factory in this town made a part I was looking for, but I lost the exact address of it. He asked me what I had to offer. I said I would pay him in souvenirs. He looked at my gift and took me to the factory. It took a couple years to establish the laboratory, but the work paid off as I was able to continue the fight for freedom of Lithuania in a different way.

|

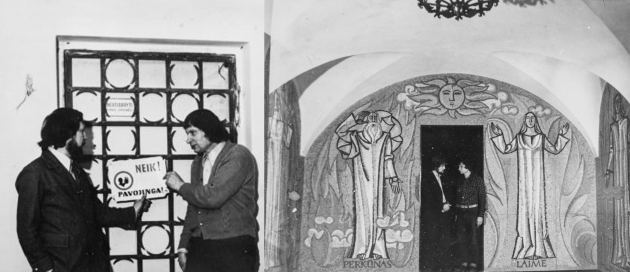

Over three decades at Vilnius University, not only did you establish an audiovisual center, but thanks to you the walls of the University were covered in murals, mosaics, frescoes, and tapestries, which also saved the old University campus from being moved to Saulėtekis.

When I was establishing audiovisual center, I was making sure that Vilnius University would be decorated. It had to be done without publicity in order not to ruin the intention. That is when the monumental art was born: frescoes, tapestries, and sculptures in the whole central ensemble of the University campus. I had to find artists with civic responsibility: the spirit that the occupant wanted to eradicate had to radiate from the vaults and walls of the University. We wanted that not only students and school children, but anyone from Lithuania and abroad who came to the University would be able to encounter our culture and history.

The ghosts of the Soviet occupants, sensing the “scent” of the new interior décor, started worrying: while the artists were creating the art, they were interfering and reporting to their leaders. The last attempt “to dig out a pit for embers under the doorstep” was a complaint about Kentra’s folkloristic nationalism that was made to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania. During the times of Russification of Lithuania, a demonstration of national pride was considered a crime.

The tapestries of Ramutė Jasudytė got us in trouble the most. When they came back from an exhibit in Italy, we wrapped them up nicely and put them on the pipes of the balcony in the Little Aula until the hall of tapestries was going to be finished. Two months later the balcony was empty. I asked everyone around but nobody knew where they were. The administration of the building maintenance department was indifferent and not going to look for a 15 meter long and 3,8 meter high unique triptych: “Horsemen in Defense of Their Homeland,” “The Messenger Swans,” and “Sisters Saying Good-Bye”. Walking down Pilies Street once, I looked through an open door into a basement and noticed a damaged “Horsemen,” stepped upon, on a damp dirty floor as if symbolizing bodies of the Forest Brothers trampled on by the NKVD collaborators on the streets of their hometowns during the years of fighting for freedom.

S. Eidrigevičius, R. Gibavičius, K. Bogdanas, R. Jasudytė, A. Kmieliauskas, S. Kuzma, R. Kazlauskas, P. Lantuch, S. Navakas, G. Pranckūnas, P. Repšys, Š. Šimulynas, V. Trušis, and V. Valius works of art in the form of frescoes, tapestries, sculptures, mosaics, murals, and graphics, thanks to their content and spirit, served over and above as silent resistance during the gloomy everyday life of the years of occupation. The art work in the University halls, hallways, and classrooms was a prelude to the Singing Revolution. It has been visited by schoolchildren, and by guests from Lithuania and abroad for years. People would stay for hours while listening to the artists’ and my stories. The memory of our history was being awoken, including national pride, civic duty and self-esteem were fostered there.

I can point out that by establishing the audiovisual center and making sure that Vilnius University was decorated, I was trying to prevent the University from being moved from its old campus to Saulėtekis. In order for the Lithuanian language to be heard in Vilnius during years of occupation, I planned to expand the University campus towards Vingis park by conjoining University buildings on Čiurlionis street with those on the old campus. My opponents would not let this happen.

You were able to accomplish all this work by being invisible, but it was much harder to stay invisible when you started filming. When I was an underaged boy, I remember you – the man with a video camera- from private and public events. Tell us please, how did you start filming?

It was very important for me to immortalize the life of science and culture at the University. The first of my movies that was publicly shown was called: “The Medium” – a student festivity at the halftime of University studies (pre-Junior year). In 1973, in the review contest for that genre of cinema of the Republic, it won second place. After this recognition, the Film Studio of Lithuania tried to convince me to leave the University and to start working for them. I did not accept the proposal, because my work at the University had not been finished. When the Baltic Way, and later January events happened, my video camera became a weapon to help destroy the Soviet Union and clear the way for Lithuanian Independence.

I received a lucrative offer for my films from U.S. TV, but did not accept it because I wanted to leave the video material in Lithuania, which would play a big role while fighting for Independence.

|

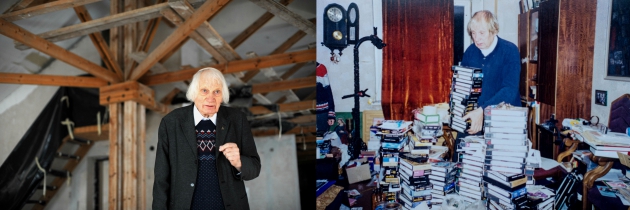

How big is your archive today? How much material is in it? Where is it? Is it accessible to the public?

It is very hard for me to answer how big it is. I want to describe it not with my own words but the words of visitors from different countries, and by giving you their impressions after they had heard about activities of our society and by watching my video material about the Lithuanian nation and its road to freedom.

In 2016, Audra Sabaliauskienė, long time director of the Institute of Culture in Denmark wrote: “Lithuanian Freedom Fighters – The Forest Brothers Society is unique not only by the accumulated archival material, which is invaluable, but also by its archive of important events, which are being relentlessly recorded by its leader Albinas Kentra, a partisan and a video annalist of Lithuanian Independence. Even more unique is the Society’s method of operation, based on personal testimonials, using authenticity to form human opinion, not only in Eastern, but also in Western Europe, where there was no experience of mass deportations, imprisonments, and torture. This is evidenced by emotional comments in the guest book of the Society. They have been left by visitors from Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, the U.S., by NATO military men, and members of Lithuanian society: students, school children, scholars of regional studies, amateurs and professional historians.

Albinas Kentra is easily searchable through the Lithuanian chapter on the coldwarsites.ne website created by Johanneso B. Rasmusseno, a Danish historian who is highly ranked in Europe and gives suggestions to academic travel agencies and institutes of culture offering specialized programs. While warmly welcoming groups, A. Kentra talks about the partisan war, where he lost his three brothers, about his own capture and imprisonment in the Gulag, and about the atrocities of the Soviet government in killing and torturing innocent people. He is happy that their blood was not shed in vain, and that the preserved spirit of Freedom was revived in 1991 when Independence was regained. This way, the most painful, scattered, and torn-out pages of the history of Lithuania during the 20th century have been restored to the history of Europe. They are being restored from live testimonials of a dramatic story of one family from Samogitia.

The activities of A. Kentra are not limited to Lithuania, but have reached his compatriots in other European countries and continents. Even before Independence, he was spreading the news about the very complicated era right after the war and during the Cold war by writing letters to the most influential rulers of the world (the U.S., U.K., Japan etc.) and getting respectful replies. It is sad that this subject is terra incognita to most Europeans, even among their closest neighbors in Scandinavia. Representatives of „Akademisk Rejsebureau“ – the Danish academic travel agency who organize special trips to the Baltics, stated that A. Kentra is an exceptional person with deep influencing powers. “Your video recordings on the eve of the January 13th events and later [...] leave an unforgettable effect on the visiting groups from Denmark. Our surveys show that Lithuania leaves the strongest impression from all three Baltic states due to your realistic testimonials. Such an open sharing of living history, so little known by the Scandinavian people, moves everyone and makes them think and want to return to Lithuania to get to know it even better.”

In 2008, Dr. J. P. Kazickas after being introduced to the Forest Brothers building and the archive housed in it, said: “It is a collection of incredible value, which portrays the real fight against the Bolshevism in cruel but real colors, and shows the conditions in which our youth was trying to achieve the most beautiful and noble goal – Freedom. What struck me the most was that it was the work of one person, without any financial support, sitting in his own room, classifying every piece of knowledge collected and recorded from that period of time. During our conversation, I found out that that person just like the Forest Brothers, despite difficulties, has been pushed to the side and left alone to do this enormous noble work with dedication incomprehensible to everyone. I saw it as a work of the Saint and thought to myself how could I possibly help him, and show him that he was not completely alone.” Kazickas stressed that the 5,000 hour video chronicle of the Forest Brothers organization is a comprehensive, realistic document about the road to Freedom of the Lithuanian nation. This chronicle proves authenticity of the events and prevents any historic misinterpretations. Thanks to the grants from the Kazickas Family Foundation, the archive is being digitized and copied in order to ensure its preservation. Every year the archive is supplemented by a couple hundred hours of video footage.

To answer questions regarding the archive’s accessibility to the general public and its dissemination, I would say that it is directly related to the reconstruction of the Forest Brothers building on the corner of Totorių g. 9 / Labdarių g. 10 in Vilnius. It has been over a decade since the governmental institutions have not been able to resolve this issue, and the building cannot accomplish its mission. In 1989, the Forest Brothers’ Society decided to reconstruct this building from the ruins of residential housing because it was from this location that 100 volunteers left to fight for the freedom of their Homeland in 1919. They would like to commemorate the memory of the volunteers not only in the Rasos Cemetery but also in the center of the capital city.

|

Source: 8diena.lt P. S. Tiesos.lt proposes to their readers: to use their experience with disseminating the Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Chronicle: After reading this article, send its link to someone else.