News

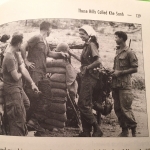

Through the years the Kazickas Family Foundation supported publishing of history books, conferences for women journalists, youth missions to record stories of the deported and victims of the war, museum educational expositions on wars. Jurate Kazickas was a reporter who covered Vietnam. In remembrance of the Veterans, here are some excerpts from Jurate's piece "These Hills Called Khe Sanh" in "War Torn".

“When I think of Vietnam, I think of the soldiers’ faces. Ungarded, innocent, smiling. They were all so young, unprepared for the filth and degradation of war. […]Some felt it was their duty to come to Vietnam. Some never stopped questioning why they were there. […]

My parents, genuinely upset at the thought of my going to war, did not offer to help with my finances. On a lark, I auditioned for a television quiz show called Password. I won the contest and, with my $500 prize money, bought a one-way ticket to Saigon and headed off to war. […]

One of the few advantages (or disadvantages ) a women reporter had in Vietnam was high visibility. […] “Are you the woman reporter they call Sam?” the press liaison growled. […] He gave me a flak jacket and helmet, and soon I was scouting the hundreds of bunkers to line up interviews with the dug-in marines. […]

Sometimes I wondered if perhaps I even wanted to be a soldier. Once after a firefight when the men were gathering the weapons of the dead and wounded[…] I picked up a M-79 grenade launcher[…] I wanted to know what it felt like to walk though the rice paddies bearing arms… like a soldier. [...]

There was more to war than killing and death. The way men bonded in war fascinated me. The comradership, the sharing of these intense moments under fire, was unlike any other human experience. […]

I stuffed my camera in my pack and crawled over to a medic. “”What can I do?” I asked. He shoved some pads of gauze in my hands and jerked his head in the direction of a group of wounded men[…] I could not imagine that there weren’t other reporters who had helped out when the situation was desperate. […]

If I found myself in a serious firefight, after it was over I would try to get out on the first available chopper to the nearest press office[ …]

“I’ve been hit… I’ve been hit,”I heard my own voice to call out.[…]

It was time for me to leave. I could not see myself in an orderly world […]but where could I go? In November 1968, I left Vietnam, I decided to go back to Lithuania via the Trans-Siberian Express. I caught a boat in Yokahoma for Vladivostok, where I boarded the dreary, lumbering train. For two weeks I traversed the vast, frozen Soviet countryside all the way to my homeland, where my long journey to a war of my own began. […]

The tangled memories of war come and go like the strange movements of that pea-size piece of shrapnel under the skin of my ankle. Some days it is so close to the surface it hurts to the touch. Other times it recedes so deep into the tissue of my body, I hardly know it’s there. […]